One of the main frustrations I’ve had with capoeira for years is the lack of a proper evaluation / examination system. I’m not even talking globally or regionally, but just within a single group. A lot of groups don’t even have any kind of system in place. A couple of years ago, I decided to do something about this within my local school and developed a framework to try and fill this gap. In this article, I will first outline the reasons why I think capoeira needs a objective evaluation system, then I’ll explain my framework in depth.

If you want to skip all the prefacing you can jump ahead to the General Idea.

Pain points

Groups award cordas or titles based on the subjective opinion of a teacher, at a specific moment in time. Other groups (mainly the larger ones) do have evaluation systems but as far as I’ve seen them, they are basic at best and leave a lot of room for interpretation. Of course, I don’t know every single capoeira group out there, so I hope at least some organizations have well thought out systems in place.

The group that I am a member of doesn’t have any sort of standardized evaluation method. And the impact on our students is absolutely noticeable. I’ll try outline the most important pain points:

- Since there isn’t a guideline for teachers, every teacher can be as strict as she/he wants. Students from one city have to be able to execute every move perfectly for their next corda, while others can go a year without barely training and still get a new corda. This causes a lot of frustration with students and incomprehension towards the decision of their teachers.

- When the teacher doesn’t have a guideline, it’s very difficult to perform consistent evaluations year after year. One year, the teacher might feel the need to be extra strict (because of pressure from his mestre, to make a point towards others, ..), while the year after he might feel very sympathetic towards his students and award cordas more easily.

- Without a consistent and transparent system, students don’t exactly know what the expectations are and as such they can’t prepare themselves properly. I’ve seen countless people getting excited to get a new corda, only to be denied one because of a remark like “yes you are good but your berimbau skills should’ve been a bit better”.

- Because capoeira is so broad, it’s not easy for a teacher to divide his time equally over all aspects of capoeira, while focusing on every student. Having a list of required skills available, the teacher can base his lesson plan on the points where his students need to improve most.

Own initiative

Thinking a lot about the lack of a decent methodology, I decided to try and come up with my own framework. It’s absolutely not my intention to conquer all capoeira groups, but rather to try and provide something my students -and hopefully one day students from fellow teachers- can benefit from. While creating my own system, I had the following goals in mind:

- It needs to be as objective as possible, independent of the evaluator and moment in time.

- Expectations and reasoning should be transparent to all students so they can use the system to their own advantage.

- It should be strict enough to guarantee a certain level of skill per corda, while also allowing some margin as everyone is different.

I worked on a rough idea for a few months before I pitched it to my close friend and co-trainer. With his help, we ironed out the details and eventually implemented a trial in our own local group. That was three years ago. The framework is still in place today, and being used not only for our small group of adult students, but for over 100 kids in eight different schools as well (which my friend manages). I’m getting more and more confident that we’ve got a solid methodology and therefore I decided to share it today.

General idea

The main idea is to have an absolute minimum set of requirements for each corda which students need to meet before the yearly batizado. It’s important to define minimum expectations, so every student can specialize in his area of interest and is not blocked by certain personal limitations. Some people will for example never be able to do aerial acrobatics, but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be able to get new cordas.

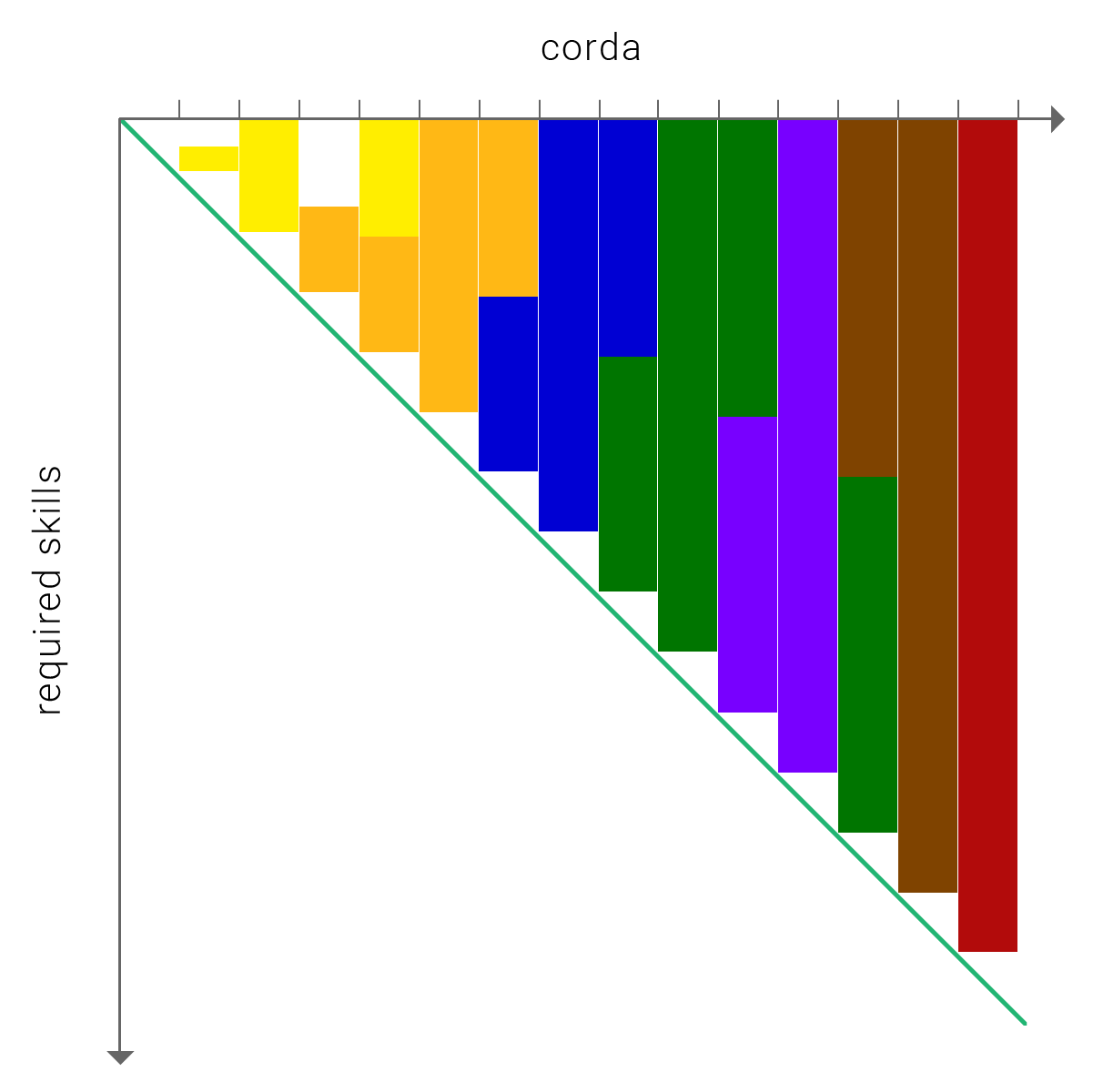

The first step was defining the requirements per corda and striking the right balance between feasibility and challenge. In the first image below, you see an (oversimplified) chart which visualizes a capoeira’s progress. The longer you train, the more experience you gain. If we flip that chart 90°, we get a vertical list of skills and a horizontal axis of cordas.

As you can see, the higher your belt, the more that is expected from you. It becomes even clearer in the visual below. Small remark: we use a belt system similar to that of groups like ABADÁ and we currently only have defined the skills up until the green belt (Graduado). For higher belts, “upper management” gets involved in the decision.

This idea can be easily translated to a spreadsheet, which forms the basis of the framework. The rows are skills and columns are the levels (belts/titles). From there on, it’s a matter of mapping out the matrix. We ultimately created a requirements list of over 100 skills and divided them into several categories:

- basic movements

- evasive movements

- attacking movements: kicks

- attacking movements: headbutts & knee strikes

- attacking movements: hand and elbow strikes

- takedowns

- acrobatics

- angola (only a subcategory becausee we are a contemporânea group)

- general knowledge

- musicality:

- clapping and singing

- pandeiro

- atabaque

- berimbau

- reco-reco

- agogô

- attendance

- soft skills

For each corda, we can now place a checkmark for the required skills.

Skill levels

Groups that have some form of examination / evaluation guidelines depend on a rather basic definition of which skills students should acquire. For example: “for your second belt, you have to be able to do a handstand“. Even though this gives some direction, it’s a very superficial requirement that’s wide open for interpretation. How long do you have to be able to stand in bananeira? Do your legs have to be straight? Is it okay to do a handstand against a wall? Do you need to be able to transition from a kick to bananeira, and back to another move? As you see, many questions arise from a simple requirement. You can’t put the same requirement for a move on a new student and a graduado expecting them to do it equally well.

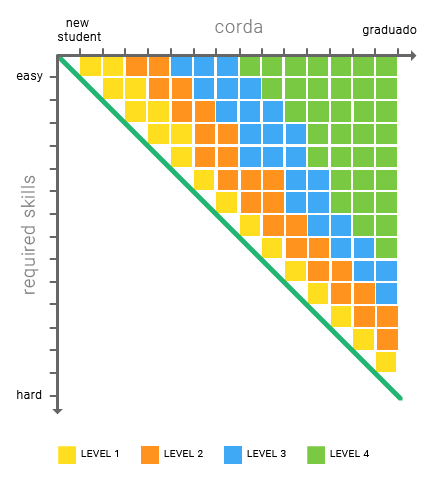

To counter that problem I introduced the concept of skill levels. Most skills are defined into four different levels (musical and knowledge skills are only true/false). For example, a beginning capoeira needs to be able to do a queixada following the Level 1 (L1) requirement. An advanced student also needs to be able to perform a queixada, but according to the L4 requirement. This allows a student to evolve within a single skill over the years. The defined levels are:

Level 1:

- Can perform the isolated movement from the basic position (ginga or cadeira).

- A low level of detail is expected:

- Can execute the movement from start to finish, in a simplified form, with tools or with stops.

- The speed with which the movement is executed is not of importance.

- The movement holds no esthetical value.

Level 2:

- Can apply the movement in the roda, from the ginga.

- A normal level of detail is expected.

- Can execute the movement in its default form, with little use of tools or stops.

- In most cases, the student is stable and holds his balance during execution.

- The movement is executed at normal speed.

- The movement holds low esthetical value (only the active body part is kept in the correct position, e.g. the kicking leg).

Level 3:

- Can implement the movement in sequences.

- Can transition from and to the movement in the roda (without the use of ginga).

- Can apply the movement in the correct game style (e.g. Angola / Benguela / Regional).

- A good level of detail is expected.

- The movement is executed smoothly, without breaks or tools.

- The student remains stable and balanced during the whole execution of the movement.

- The movement can be performed at higher speeds.

- The movement has a good esthetical value (except for some details, all body parts are in the right position).

Level 4:

- Can transform the movement (e.g. by adding a floreio, as a feint, to better fit the style of the game, …)

- Can execute different variations of the movement (e.g. with/without hand on the ground, end in another position, …)

- A high level of detail is expected.

- The movement is executed smoothly, without breaks or tools.

- The student has full control over the movement and is stable and well balanced at all times.

- The movement can be executed at different speeds.

- The movement has a high esthetical value (all body parts are held in the right position throughout the whole movement).

Also, this gives some flexibility in the list of skills. It’s sufficient to just define “queixada” as a skill, even though there are several variations on the kick. You don’t need to define the variations as they are implicitly contained in the Level 4 definition.

Every level has its own color so that a requirement is easily identifiable. With all this in mind, we can recolor our previous visual:

As you can see in the example, for the first few cordas you only need to know the basics of a few skills. When advancing, you are expected to perfect more and more skills while also learning the basics of harder skills.

Time is key

The defined requirements per corda should be in proportion to the time a student has to develop these skills. Typically this is one year between two batizados. Make sure it is feasible to achieve the expectations. If getting to the next corda requires a lot of new skills, then you should consider dividing requirements over multiple belts or making it a hard requirement to wear the corda for multiple years. We’ve done this on all intermediate and higher cordas, because it gives students the time required to mature in capoeira. Even if you have someone extremely talented that checks all the boxes, that doesn’t necessarily mean he has collected all the “baggage” which you get from training and playing over a longer time.

By adding a “two year seniority” requirement starting from the orange belt, it takes around ten years to achieve the rank of Graduado. This is a realistic timespan that a lot of groups use and which allows the student to mature in capoeira.

Cordas are never skipped

We always make it very clear to our students that no one can ever skip a belt. Skipping belts is done in a lot of groups and even though it is often frowned upon, many teachers still consider it a gift they’re handing out. But only the opposite is true. No matter how talented you are, skipping a belt always has a negative impact on your self-confidence (in both ways) and you are denied the chance to grow in capoeira as discussed above.

Even if someone couldn’t make it to the batizado one year, we never award two belts within the same year.

Soft skills and attendance

While almost all competencies are focused on movements and music, I found it important to also include requirements on soft skills. These define how a student is expected to behave in the capoeira community. Some examples of competencies we have included are:

- The student has respect for his teachers and fellow students.

- The student is not overly aggressive in the roda and knows how to control his temper.

- The student is a good ambassador for both the school and the group at internal and external events.

- The student can lead a warm-up during class.

- The student can lead a roda.

- …

We also put a requirement on attendance, to make sure a student actually trains in the school on a frequent basis and makes an effort to visit events. Some examples are:

- For the first three belts, you need to attend at least one class per week. For higher belts a minimum attendance of two classes per week is required.

- For the first three belts, you need to attend at least one internal event per year. For higher belts, this goes up to two, three and five events per year.

- Advanced students need to have visited at least one external event since their last troca de corda.

- …

Scoring

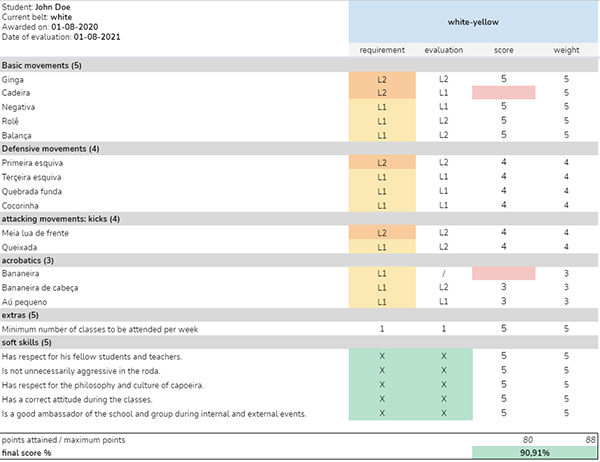

Once I completed the matrix the next step was to include a scoring system which would allow us to easily fill out an evaluation and get a total percentage. A student needs to get at least 90% to pass his exam. This is high, but remember we are always talking about the minimum requirements for a belt. Since some skills are more important than others, we applied a weight to each category which is a number between 1 and 5.

If you pass a skill, you get a score equal to the category’s weight. The total percentage is calculated by dividing the attainted points by the maximum number of points.

For the first belts the evaluation sheet is a very short list where the students need to pass almost all skills to get 90% or higher. For the higher belts, the list includes most skills, giving them more margin to pass since the impact of a single skill on the total score is a lot lower.

Transparency

One of my key objectives was to offer transparency towards students so they can properly prepare and know exactly why they are denied a new belt if that happens. We do that by:

- Making all spreadsheets available to everyone. All members can download and study the evaluation forms.

- All guidelines and rules are described in a document which is also shared with everyone.

- We organize a pre-evaluation 3 months before the yearly exam, using the same methodology. Results and score cards are shared with each student individually. If necessary, we also provide personal feedback. The student can use this input to work on the points where he is still lacking so he can better prepare himself in the next months.

- Students that are not interested in belts and ranks, can opt out of the evaluation process. They will not get a belt, but it removes a lot of pressure on people who just want to have fun and don’t take their sport too seriously.

- We encourage our students to perform a self-evaluation at least once a year. We can then compare their own evaluation form to the one we as teachers have filled out. This can highlight important misconceptions on certain skills or expectations

- E.g. a student might think he is a Level 4 on queixada while the teacher might’ve marked his skill as a Level 2.

Downloads

I’ve made my template freely available for anyone to download. You can use it as an example or as a starting point for your own classes. Click the links below to download the file:

Conclusion

Reaching the end of the article, I realize it may look like a complex setup that takes a lot of time. I wanted to explain every aspect carefully, but in reality it is quite simple. Once you have your requirements per corda mapped out, it’s a matter of filling out each student’s form once or twice a year and discussing the results with them.

As I said earlier, we’ve been using this framework for three years now. We’ve made some small adjustments in the requirements, but aside from that very little has changed since it is working so well. We’ve noticed that we as teachers are a lot less subjective when evaluating members since we have to play by the rules now. Sometimes that meant we needed to be strict and deny someone a new corda because they clearly didn’t check all the boxes, even though we really wanted it for them.

I can’t say yet what the effect in the long run will be, but essentially it should help maintain or even improve the quality of our students’ capoeira. Of course, an evaluation is only meant to monitor quality and progress. To help someone become a great capoeirista, the only thing you can do is be a great teacher and offer interesting, challenging classes.

Disclaimers

I realize this is a delicate subject. Some say capoeira is a free art and can’t be defined by rules, while others try to help capoeira by adding structure.

While reading this, I know a lot of you will argue that a teacher has to know their students and shouldn’t need an “evaluation plan”. I absolutely understand this, as I teach a very small group (<15 people) myself. But, every year someone manages to surprise me (either in a good or bad way). And even though I know my students very well, having a moment during the year where everyone is focused on reviewing their skills really helps to pinpoint problems and opportunities.

Another important point many capoeiras make, is that you shouldn’t focus too much on which corda you are wearing. “It’s only to hold up your pants”. Over the years, I too have come to rationalize the value of a belt but nonetheless I am part of a group that uses belts to rank their students. Because that was my choice, I embraced the grading system (although not always with enthusiasm).

I’ve designed this framework to be universally applicable, but you always have to place it in the context of your own group. If something doesn’t really make sense for your organization, change it to better fit your needs.

— Vinho

Wow this is impressive.Thank you for sharing this ! I am a student myself and I looked up the topic of the graduation systems in “regional” groups since I noticed how much bitterness and confusion batizados can bring up.

Despite teachers having a chart of requirements for passing each cordao, it appears to me that there is always a subjective factor that cannot be put into a chart.Things such as if the teacher prefers a style of play (more acrobatic, more “aggressive”, more”technical”).

Could you tell us how it is going so far ? Also, if I may ask, to you as a teacher, can you tell us what is the value of the graduation system in “regional”?

Many thanks and sorry for my English, it is not my first language.

Hi!

I believe that the playing style is inherited automatically by the student, since he trains within a certain group which has its own style. Next to that, everyone develops his own personal style. For us it isn’t really important whether someone plays a more acrobatic game than someone else, as long as they master the skills separately. There are exceptions of course when a student is too agressive or plays too much on his own. Those things are indeed hard to quantify in a score, but we always leave room for separate remarks on the exam which can be taken into consideration as well.

We’ve had evaluations in April and it went again really well. We learned that we as teachers needed to focus on some specific moves during the classes, since almost everyone was failing on those skill requirements. Next to that we noticed we really wanted to give some of our students a new grade even though they didn’t pass their exam. We just felt they deserved it because we feel sympathetic towards them and we’re friends. But we followed our own rules and that prevented us exactly for a major pitfall: awarding someone a corda for an emotional reason even though that student is clearly not ready.

So for me, yes, the system works as it helps me as a teacher to stay objective.